Earth Moon Earth (EME) Lab

Building Reproducible EME Stations

While experimenting with various long distance communication modes in amateur radio world, Earth Moon Earth (EME) stood out as one of the most challenging, rewarding, and technologically all encompassing projects. We started building a EME station for ourselves and share the love with the world so that others can use what we build, kids can learn about space, weather, radio communication, electricity, and technology enthusiasts can join in building reproducible EME stations, DX chaser facilities, comprehensive weather monitoring and analysis capabilities, space exploration through electromagnetic waves and unleash curiosity and creativity. EME is not new, but we now have more advanced computational technology, more advanced Digital Signal Processing, and the new Software Defined Radio (SDR) technology, we are taking a baby step forward and redoing most aspects of EME by using technologies we have at our disposal. The basic background of EME can be found here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth–Moon–Earth_communication

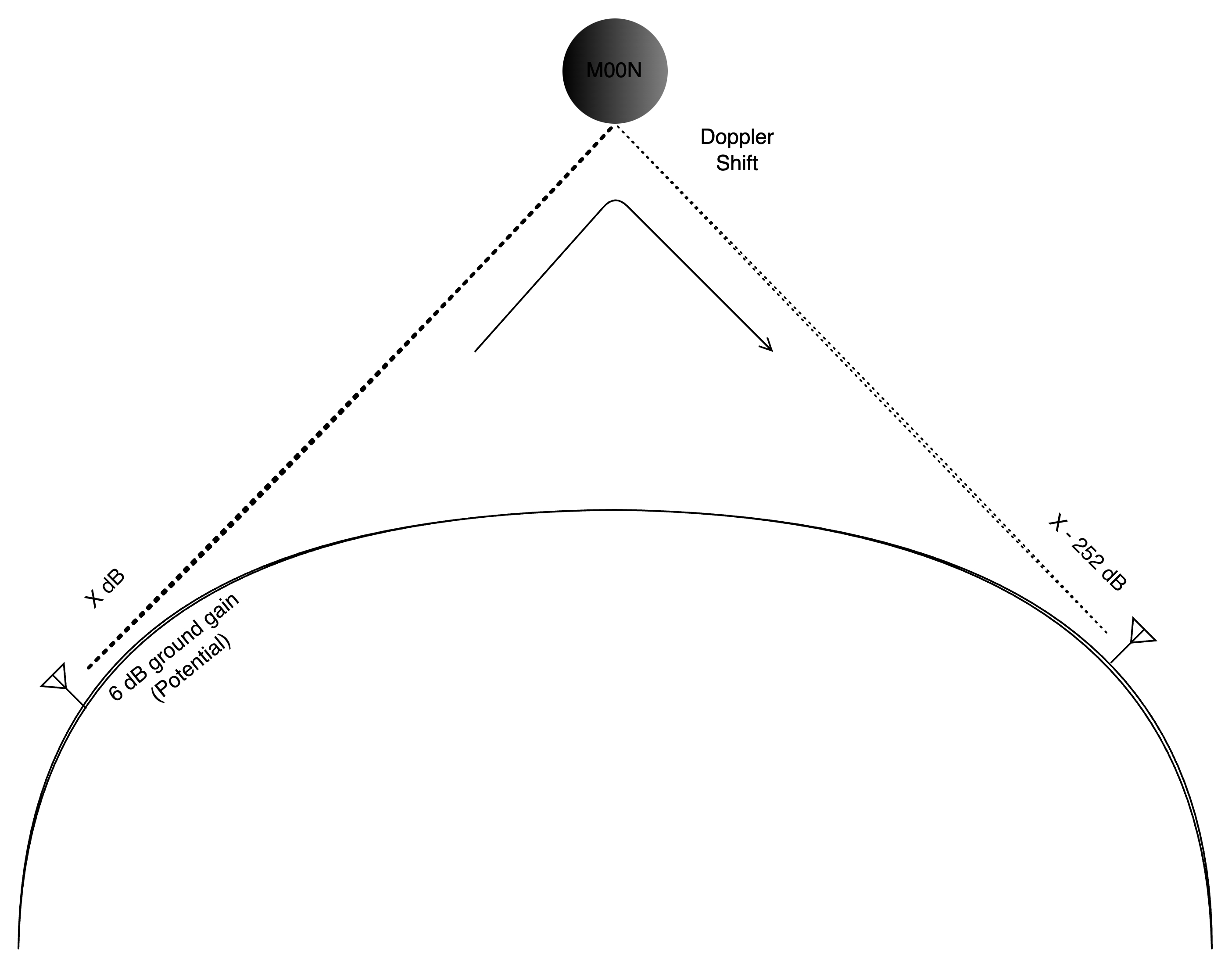

The major fun and main challenge of EME communication is huge loss in reflected signal strength. It is ~252 dB. Every 3 dB loss halves the signal strength. So 252 dB loss is equivalent of 1 unit getting reduced to 2-84 unit. And then comes the latency. The signal propagation time from Earth to the Moon and back ranges between 2.4 and 2.7 seconds. These limitations make EME technically very challenging yet rewarding. The equipments need to be capable of dealing with efficient signal propagation, weak signal reception, and decoding the weak signal meaningfully. We can group the challenges into three categories. Limitations, choices with trade-offs and QSO planning. Since we will be using the term QSO a lot, for those who are not familiar with Q-code, it means a confirmed bidirectional communication or successful contact between two parties.

Limitations

- Loss of signal strength in full path propagation

- Noise accumulation

- Faraday rotation

Choices with Trade-Offs

- Choice of the frequency

- Choice of polarization

- Choice of Antenna Size, Type and Numbers

- Choice of communication mode (voice/CW/digital)

- Choice of Radio

QSO Planning

- Readiness of both QTH

- Polarization matching

- Position of Sun wrt QTH and Moon

- Position of Moon wrt Earth

- Position of Moon wrt QTH

- Establishing QSO time

Fig-1: EME Propagation

Let’s call the above mentioned limitations, trade-offs, and planning as concerns collectively.

Addressing the concerns

The concerns are not addressed in the same order as they are listed above.

Dealing with loss of signal strength

To begin with, let’s make sure we can receive moderately strong signal from large known EME stations. That should be our first goal and then a clean enough and powerful enough transmission that can be read by large EME stations. This is the beginnning, before we become large powerful EME station.

Even with a moderately powerful EME station at the other side of the QSO, the received signal is going to be weak, so we need machinery to deal with it. Let’s go with the proverbial Ham saying, “If you can’t hear, you can’t work.” That demands a good antenna.

A good EME antenna system

A massive array with 9 antennas? I wish but that’s not a reasonable start. An array of 4 144MHz Yagis? That’s great but still not a modest beginning. How about only one 144MHz antenna?

Let’s assume if we can receive and read a moderately powerful station, that station can read us by the virtue of having better reception machinery. With that, let’s focus on improving our reception.

Considering a single 144MHz Yagi-Uda antenna

How about a 9el 144Mhz Yagi? This is seemingly impossible. But we have examples around the world using this types of antennas in EME contacts with good success. Let’s examine that possibility with some basic math. Let’s see if we can copy our own echo using this type of antenna.

The mode (voice, CW, digital) of choice will determine an acceptable SNR in order to copy the transmitted information. Let’s first see the link budget involving SNR

SNR = Pr - Pn OR Pr = SNR + Pn

Pt = Pr - Gt - Gr + L

Pt and Pr are transmitted and received power in dBW. Gt and Gr are transmission and receiving antenna gains in dBi. L is EME path loss in dB. Pn is the receiving noise power in dBW.

Let’s do some substituion from the above two equations. And an assumption that receiving antenna gain Gr and transmission antenna gain Gt are the same. i.e. Gr = Gt = G

Pt = SNR + Pn - 2G + L

Pn = 10 log(kTsB)

kTsB is the received noise power. Pn is the received noise power in dBW.

k = 1.38 x 10-23 Joules/K and is called Boltzmann’s constant.

A typical system noise temperature Ts = 100K.

What should be the value of B? For digital mode, JT65 is 2500 Hz, for CW it is 50Hz.

So the received noise power in dBW is -176.6218 for JT65. For CW it is -191.6115. As we can see, noise power gets lower with lower bandwidth. But then SNR tolerance varies widely. The difference in noise power in dBW is about 15 dBW favoring CW. Where as the minimum SNR needed for JT65 is -24 dB and for CW it is 3 dB. Difference is 27 dB favoring JT65. Combining these two JT65 have about 12 dB advantage. Which is 16 times more transmission power for CW. I don’t know how Joe Taylor found it 10 times in his calculation. But hey he is the JT. May be difference in system noise temperature while operating in CW! Anyway, since we established digital is advantageous in terms for transmission power needed, let’s see the real number i.e. the real transmission power needed for the transmitter for JT65.

Let’s consider transmitter and receiver has identical antenna. A single 9 element yagi at each side. Such antenna typically has the gain G = 14.1 dBi.

Now let’s focus on the value of L.

L = 261.6 + 20 log(f / 432)

With f = 144 MHz, L = 252 dB.

Let’s revisit the equation Pt = SNR + Pn - 2G + L

Substitute the values obtained so far. Pt = -24 + (-176.62) - 2 x 14.1 + 252 = 23.18 dBW

23.18 dBW is equivalent to 208 watts of transmission power. We need ~208 watts of transmission power in order to copy self-echo in digital mode using JT65. CW would require 16 times more power. This is for self-echo or communicating with an identical station with an identical antenna and same transmission power of 208 watts.

Now we have baselined what the antenna and transmission power should be for a EME station capable of self-echoing using a digital mode using JT65. This baseline setup can be duplicated and they can communicate with each other too using JT65. Let’s now examine whether we can enhance the station’s capability without increasing transmission power, and find out if we can reduce transmission power while still achieving the goal.

Techniques to acquire additional gains

The goal is to not increase transmission power, but decrease if permissible.

Let’s say we have Station A and Station B. In bidirectional communication, antenna gain at any station will improve received power in both directions. This means antenna gain at either side adds up to the link budget and reduce the requirement for a minimum power budget. If we add n dB of link budget at either side of the link, i.e. either station, power budget can be reduced by n dB at both sides totaling a 2n dB power reduction, whereas increasing the power budget to one side of the link i.e. at one station only helps the other station to receive higher signal strength but does not help its own station receive better as the other station did not add any additional power for transmission. So if we add anything to the link budget, that gives us an opportunity to work weaker stations deficient in both transmission and reception.

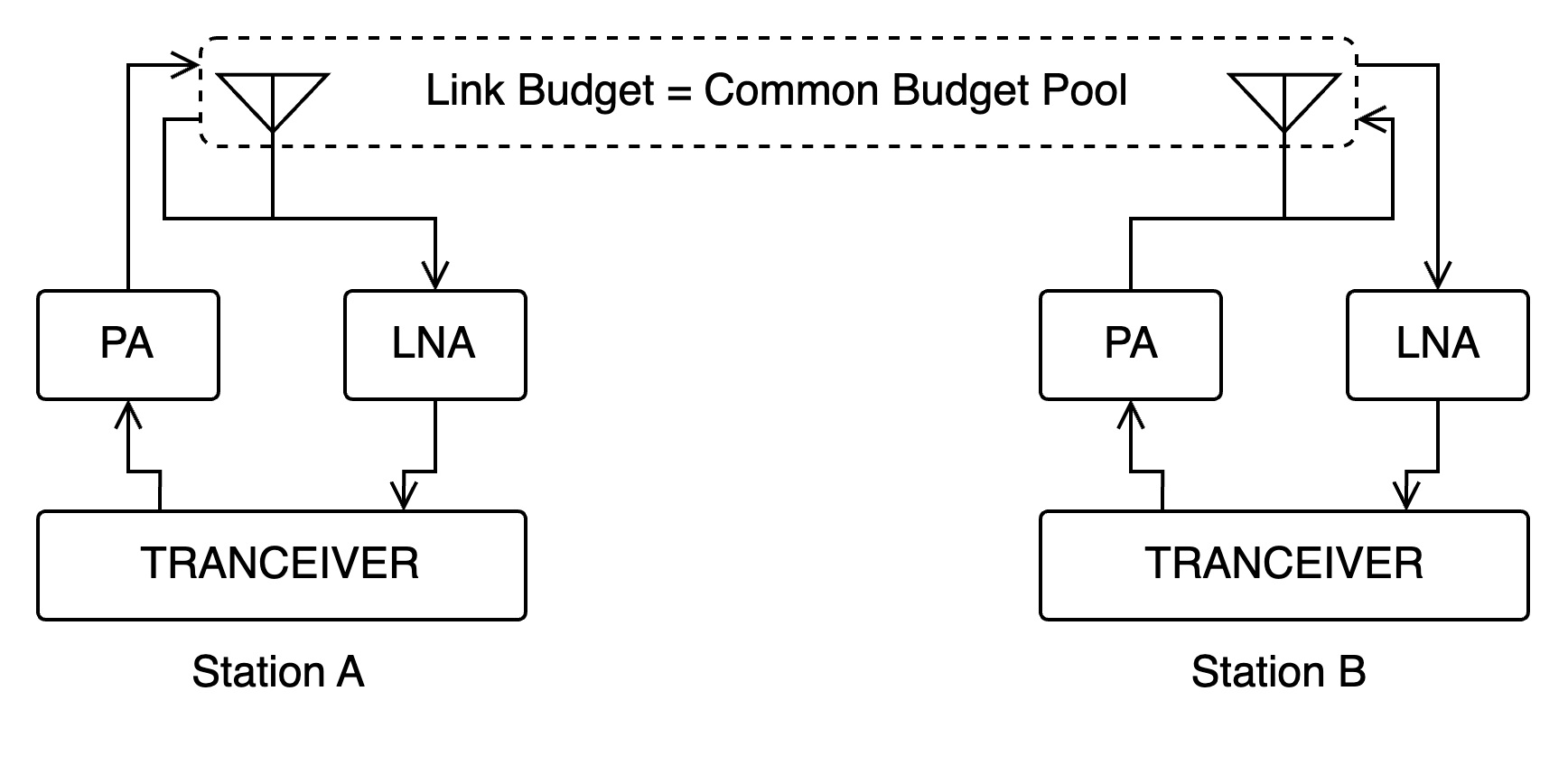

Fig-2: EME Link Budget

In this diagram, if we increase gain g to the power amplifer (PA) at station A, it makes the station B hear better. But that does not add any receiving gain benefit to the station A. And the same holds true reciprocally if we increase gain of the PA of station B.

Similarly, if we add a LNA to increase receiving gain g at station A, that does not add any receiving gain to the station B. And the reverse holds true.

Let’s assume that we have 2 identical stations optimally setup to establish bidirectional contacts between themselves. Now we reduce the overall gain for both the stations such a way that they are just a bit short in gain for a successful contact. Let’s say that gain deficiency is g. If the station A can add this gain g to it’s PA, it can reach station B. Station B in the other hand, can’t reach station A just because station A added gain to A’s PA. In this situation, B can hear A but not the opposite. Instead of adding transmission power, if A adds gain g to its receiving capability through LNA, A can now hear B, but B can’t hear A. So adding gain to transmission or receiving circuitry (PA or LNA) adds only one way benefit. Instead of adding any additional transmission gain or receiving gain through PA or LNA, if we add this gain g to either sides of the antennas, A and B now would be able to make successful contacts. In other words, antenna gain is a shared budget and has a bidirectional effect, station gain (PA and LNA) is local budget with unidirectional effect.

Ground gain, where does it go?

If you are endowed with a very good RF ground, like a big water body, a moist field, a marsh land, there will be some ground gain. Considering the transmission path and receiving path are same with direction reversed, the ground gain is added to both transmission and reception even when the ground is at one side of the two communicating stations. So a good RF ground is part of shared link budget.

Ground gain can be ~6 dB for an excellent RF ground and optimally positioned antenna over the ground. With same power transmitted a station can reach to another station with 6 dB weaker receiving antenna gain. Or the transmitting station can reduce the transmission power to one quarter of reference power. Our calculated reference power for the reference setup was 208 watts, with 6 dB ground gain that power can be reduced to 208/4 = 52 watts. That’s a great gain. If more successful QSOs with weaker stations are desired, reduction in power is desirable. With higher transmission power at one end would make weaker stations to hear us but may not be able to reach back and complete the QSO.

References

- Optimized Small-Station EME X-pol at 432 MHz by Joe Taylor, K1JT. https://wsjt.sourceforge.io/Optimized_Small-Station_EME.pdf

- Ground gain and radiation angle at VHF at QSL.net https://www.qsl.net/oz1rh/gndgain/gnd_gain_eme_2002.htm

- Q Codes https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q_code